Listening and Experience

BACKGROUND

Why do we like certain music or sounds, and not others?

More fundamentally, how is it that we actually experience sound in the first place?

I’ve always been drawn to music. Since 1979 my taste has broadened significantly. I now listen to and compose music that I might not have understood or appreciated before then. Kraut rock? Deep ambient? Tuvan throat music? (Weird, but fascinating and surprising.) Algerian Rai? Dub techno? South African house? Industrial? Ethiopian guragegna? Jazz fusion? Malian blues? American roots music? Prog rock? Yes, please!

Aside from mere eclecticism – and perhaps a small dose of curiosity – why do I enjoy all these genres of music? Why do so many people listen almost exclusively to just one style? What is “good” music? Is there something to be learned about all of this from how we experience sound? (And… can I ask any more questions in the Background section of this blog entry? That would be a '‘Yes.’)

Over the past few years I’ve taken a deep dive into Theravadan and early Madhyamaka Buddhist philosophy and psychology. These schools emphasize not only logic, but direct experience. They are not belief systems. A combination of study, contemplation / investigation, and meditative practice breathes life into their models of experiential reality. This is in sharp contrast to many neurological models of consciousness, which tend toward materialist reductionism and ignore or dismiss the role of experience. The associated Western philosophies swing either to materialism, idealism, or something in between (monism, anyone?) that I’ve found for the most part unsatisfying.

In what follows we’ll take a journey into the mechanisms of consciousness via a functional model of mind to understand the underlying processes – but not the ontological nature – of experience. In other words, we’ll look at what the mind does, not what it is. Special attention is paid to sound and music as a model problem.

A FUNCTIONAL MODEL OF MIND

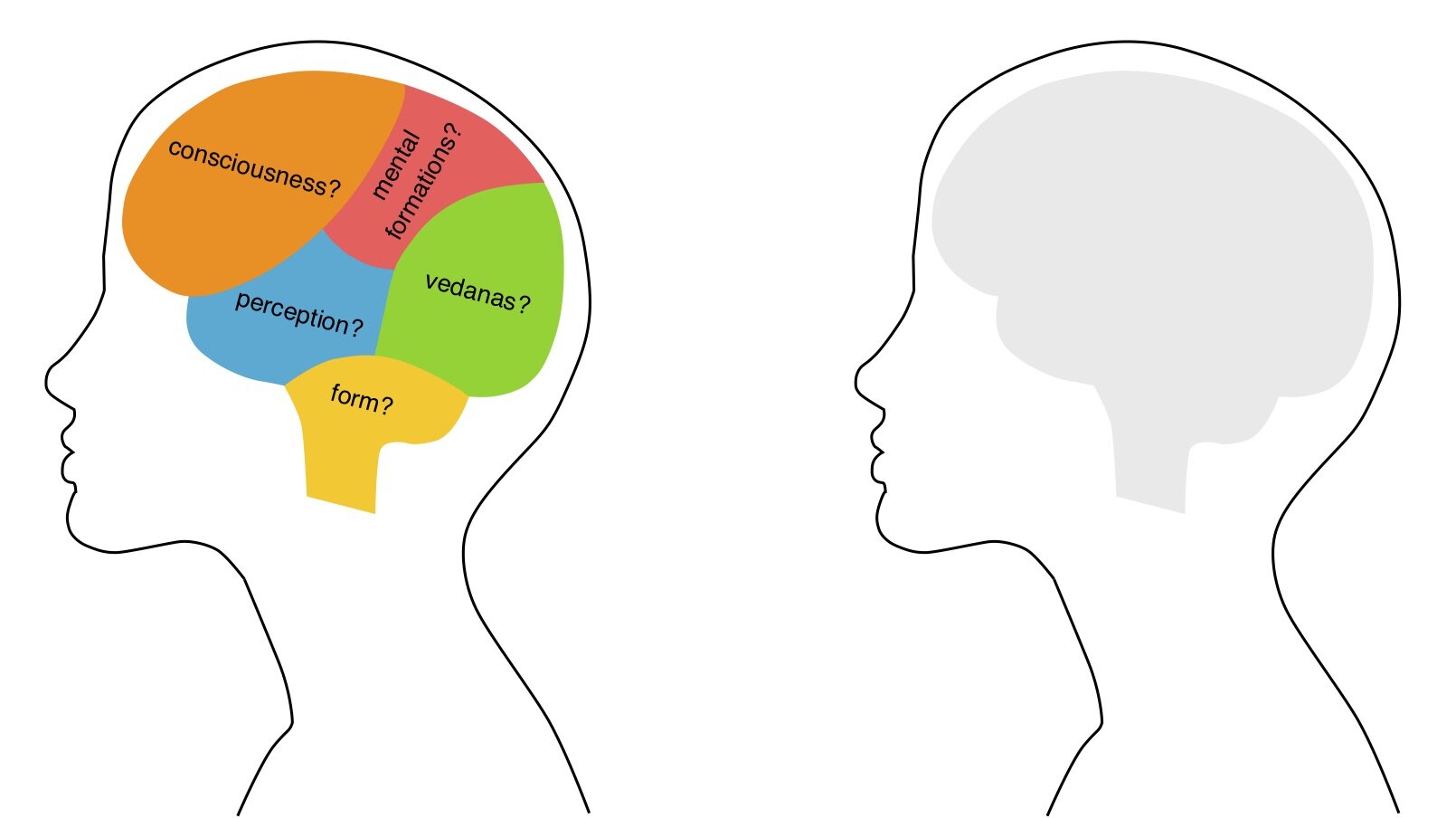

Let’s go under the hood and consider the activities of the mind using a model of experience called the Aggregates. The aggregates are a teaching model used in many Buddhist philosophical traditions.

The word aggregate is a translation of the Pali word skandhas, which means “pile” or “heap.” The aggregates are phenomenal processes organized by causes and conditions. They are depicted together in a heap in the figure below. They comprise five elements: Form, Vedanas (often translated as “Feelings,” a term we won’t use since it confuses this element with emotions), Perception, Mental Formations, and Consciousness. The aggregates encompass all instances of each element: past, present, or future. In modern parlance they are a modular model of mind. However, while most modular models attempt to represent behaviors, the aggregates model experience.

The Aggregates.

The Aggregates are a reductionist framing of mental processes organized in functional groupings. It’s best to think of them as verbs – or, perhaps gerunds – rather than as things, despite their being labeled using nouns. It is also best not to reify them; while we might think of them as corresponding to specific brain regions, as (vaguely and inaccurately) suggested in the left figure below, the right figure is perhaps more accurate in light of their distributed and transitory nature. This reflects recent research on perception and awareness, which ties these functions more to how global signals in the brain organize themselves over time.

Moving away from reification.

Over the course of our lifetime we’ve experienced a nearly uncountable number of thoughts, sights, sounds, and tastes, accumulated a vast bank of memories, undertaken a plethora of activities, and spoken enough words to fill volumes. The advantage of the Aggregates model is that it synopsizes these experiences using a modest number of mental processes that are present with all of us. It keeps us from getting bogged down in the vast ocean of content: our ‘stuff’. And it points to a universality shared by us all irrespective of gender, race, age, or socialization.

FORM

Form represents the world as it is presented to the eyes, the ears, the taste buds, the nose, the nerve endings in our skin and viscera as well as our senses of balance and proprioception. It also includes the mind in its role as a sense organ of thoughts and emotions, making it the sixth sense in Buddhism. Form is the immediate sensory experience or mental impression of objects within our sensory field. In the broadest sense you can think of form as including all matter, all the sense organs, and all sense impressions arising from them. How else do you experience the world except through these? (This is not merely a rhetorical question!)

Form describes an input space for the aggregates. If you are mathematically inclined you can think of form as their domain, while experience is their range. For hearing form encompasses the source of sound or music, the sound waves that impinge upon our ear drums, the vibratory response of the ossicles that drive fluidic waves within the channels of the cochlea through the oval window, the frequency discriminative function of the sensory receptors in the cochlear hair cells, and the portion of the cranial nerve that sends nerve impulses from the ears to the brain. The other senses can be similarly represented. In total these are the six sense ‘doors’.

VEDANAS

The vedanas define the affective quality of every instance of sense contact through each of the six sense doors. This affective quality – sometimes called the feeling tone of sensory contact – is experienced immediately and automatically in one of three ways: pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. Neutral is often expressed as “neither pleasant nor unpleasant” to reflect a range of affective feeling that lies between pleasant and unpleasant. The vedanas encompass the subjective impact or the ‘how’ of a sensory impression.

It takes practice to discern the arising of these affective qualities; usually we are aware of sensory experience as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral only after the fact in light of our reactions to them. But this investigation is possible because the vedanas are the basis for forming our likes and dislikes, which we can be aware of.

Certainly the nearly instantaneous nature of these affective feelings was evolutionarily useful. If you were crouched in a hunting blind on the savannah 100,000 years ago and heard the growl of a lion, best to tap into the ‘flight’ part of the fight, flight, or freeze response and run away as fast as possible. But nowadays, with fewer lions waiting to pounce, we more often see likes and dislikes after they become the causes for reactive emotions like frustration, distaste, fear, or excitement – if we are aware of them at all. Forms that have neutral feeling tone lead us to ignore aspects of our experience, overlooking things that don’t appeal to us – for example, very slow moving, atmospheric, or light music that might at best be labeled aural wallpaper or furniture music. Yet all of this is part of our experience, neutral or otherwise.

We might assume that the feeling tone of a sense contact is a property of the object: the thing we hear, the food we taste. When we hear particularly beautiful music it’s easy to think that beauty is an inherent property of the work. We’d likely conclude that everyone else would experience it in the same way; I mean, it’s a beautiful composition, right?

While my taste in music may be similar to your’s, it’s likely different than most everyone else’s. Because of our socialization and past experiences feeling tone becomes a highly personalized response to each sense contact. It’s a shorthand that we use to prioritize what we want more of, less of, or what we ignore. Since the affective qualities of experience are based on imprints from past experience, being aware of their personal and relative nature allows us to be mindful of overlaying our own values onto form such as sound or music or anything else as if these were inherent qualities of the objects.

The Buddha pointed out that there are three roots that underly our unhappiness or dissatisfaction: craving (e.g., grasping, clinging), aversion, and delusion. This overlaying of our values to establish (i.e., reify) or reinforce inherency – here, an assumption that qualities of experience are inherent properties of objects – is a facet of the third root, delusion.

PERCEPTION

Perception is the process that recognizes, categorizes, and labels form, such as recognizing a piano as a piano, the sound of birds, or the color blue. Perception and the vedanas both depend on the sensory inputs of form. While the vedanas connote an affective feeling of an object, perception discerns the object’s features, a type of sorting that separates things from an otherwise ambiguous sensory environment. Perception thus provides the “what” of experience: what is heard, what is thought, what is seen, etc. It too is largely automatic.

Perception relies on memory to provide the database of prior percepts that are used to perform object recognition. Since objects are discriminated in light of prior percepts perception is 're-cognizing’ them.

When there is no prior percept to draw upon perception can bring other processes to bear. These are enacted by a pleasant or unpleasant feeling tone depending on how we characteristically respond to new or unknown things. This updates the percept database by scrutinizing a novel object (directing attention and sustaining it on the object) to discern its features for future re-cognizing. We’ve all experienced this before. For example, if we hear an unfamiliar birdsong, our curiosity (pleasant or unpleasant feeling tone giving rise to grasping) leads us to dwell on it (cling) in order to distinguish its distinctive features for future use in recognition, or to look up later in an app that catalogs birdsong. You’ve probably noted that this process takes longer than recognition of a known sound.

Perception is happening while you read these words. At a basic level your eyes are just receiving differing amounts of light over their fields of view. These variations of light and dark are perceived as patterns, then as patterns corresponding to letters, then as groups of letters that comprise words. If what you see is interesting, the vedanas lead to (e.g., condition) grasping that makes you continue looking at the screen (clinging) until you perceive words, which are concepts. But there are no words on the screen in front of you, just varying amounts of light and dark. There is no inherent meaning in these visual patterns, they are merely encodings. If the words continue to interest you (pleasant feeling tone arising from the conceptual content we infer from these patterns) you’ll keep on reading (a volitional action, which we’ll investigate in the next section), and the processes continue. These are just things that happen, and they’re happening right now.

Perception is happening when you listen to music. At a basic level your ears receive differing amplitudes of sound over time within an acoustic environment. These variations between soft and loud sound pressure are spectrally separated in the cochlea, then perceived as tones, as patterns corresponding to notes, chords, or percussive sounds, then as groups of these elements that comprise songs or parts thereof, such as melody or chord progression. The vedanas lead to grasping that leads on to further listening until you perceive recognizable sounds that you might label as “C” or “G-flat” or “guitar” or “singing” or “snare drum” or “birdsong” or “leaf blower.” If the sounds interest you (pleasant feeling tone) you’ll keep on listening (a volitional action), and the processes continue. If not (unpleasant or neutral feeling tone) you move on to something else. These are just things that happen, and they may be happening right now.

Through perception we constantly pick out things and naming them: birdsong, car horn, food processor, speech, the sound of a trumpet. Sound objects themselves don’t have names – names are assigned in light of past experience and social convention. Musical sound objects themselves don’t ‘have’ notes. Notes like ‘C’ or ‘F#’ are conceptual labels we assign to experience. Consequently, perception includes an act of conceptualization through labeling. This labeling is a basis for the proliferation of thought, a mental process we’ll consider below.

MENTAL FORMATIONS

The aggregate of mental formations – sometimes referred to as volitional formations or mental factors – comprise the mental imprints and activities of the mind generated in response to an object, such as grasping, clinging, aversion, and attention. They include processes that initiate ideation, speech, and both mental and physical action. In contrast to the other aggregates these factors are intentional, caused by and causing other processes. (If they were not intentional but purely automatic then there would be no choices, such as the choice to become free of grasping, clinging, aversion, and delusion. Yay, free will!)

For example, intention arising in response to contact (defined below) and grasping moves attention to a sensed object, like when you bang your toes on a curb, then subsequently (and suddenly!) become aware of the attendant sensation. Ideation and conceptualization provide context to experience and an impetus or opportunity to act. We may be listening to music on a device that presents a playlist, and can choose to continue listening, skip to the next track, replay a song, or restart the playlist from the beginning. Or we may notice two people fighting and choose to intervene.

I’ve spent quite some time investigating intention. I initially posited that intention was higher in the pecking order than other processes like ideation or emotion. But intentions arise, abide, and cease like any other aspect of experience, responding to causes or conditions present at that moment. This became obvious when I stubbed a toe while climbing a set of stone stairs; see example above. Attention was immediately drawn to the attendant sensations of pain, and I was moved from knowing visual objects (where I was going) to a very sharp and clear knowing of a rather painful body sensation. There was no conscious act that moved attention to the sensation of pain; it just moved. Intention was a causative mental factor in my toe-stubbing example, leading me toward the sensation of pain. In that way, intention just happens in response to causes, conditions, and our conditioning.

What puzzled me is that this movement of attention toward the sensation of a stubbed toe occurred unconsciously. I didn’t instruct intention to manifest and move attention toward the toe; it just did. After many months of investigation, it became clear that intention in general arises in response to any number of causes and conditions. To consciously cause intention to arise and move attention to an object is merely intention responding to an idea (for example, music as a focus of experience in the present moment), an idea’s feeling tone (we recall that the sensation of hearing music is pleasant – even calming, or perhaps exciting), and grasping after something (I want to listen to this music), whereupon our attention moves to the music and we become aware of sounds.

Working backwards from this example of “intention-ing,” recall that ideas are concepts, and as noted above concepts arise from the process of perception as well as other mental processes. This is happening all the time. The ideas that arise, the choices that are made, the actions that are taken, and their frequencies and patterns are what we commonly refer to as someone’s personality, which is comprised of habit patterns. This is just the day-to-day, moment-to-moment distribution and prominence of the various mental formations as they intersect and evolve. What we habitually intend toward becomes, for example, our taste in music.

CONSCIOUSNESS

In the West ‘consciousness’ conventionally means the operation of the mind in general. In the aggregate model consciousness merely refers to being conscious of something. Other words for consciousness in the aggregate model are bare knowing or apprehending. Keep these definitions in mind while reading the balance of this post.

Consciousness is the simplest knowing of an object, and it initially precedes perception. When a sense impression arises it is conjoined in a moment of knowing referred to as contact. Early in my meditation practice I found myself knowing that a transient sound had occurred prior to consciously hearing or recognizing it. I would first notice the sound’s presence, and also its direction. I would sit and observe sounds, and discovered an internal trigger and direction finder constantly noting and tracking pings in the baseboards, pops or creaks of floorboards, or the chittering of birds outside the window, all occuring prior to actually having the experience of hearing them. This likely reflects my long-standing interest in music, and in critically listening to it for much of my life. The meditative experience of contact demonstrates that sound contact – the arising of sound-consciousness along with sound – occurs prior to sound discrimination via perception and subsequent mental processes. Sound is a wonderful object to explore.

Every moment of experience has an element of knowing. Consciousness provides a sense of cohesiveness to experience that would otherwise be just a series of rapidly changing and disconnected percepts. For example, when hearing a note of music we can remember what the previous notes sounded like; this is how we discern melody. If there had been no knowing of the note’s sensory experience we could not have formed a memory of it, nor could we know what the note might be compared with to discern melody (or a lack thereof). We compare against references to ascertain context, and those references must be known. (And how are those references formed? By experience, upbringing, and culture.)

Similarly, if right in this moment we attend to our heartbeat we can know that our heart is indeed beating. If attention is moved to something else, then returned to the heartbeat, we know that the heart is (still) beating. We know this because of memory, an aspect of knowing and apprehending. Conscious knowing contributes to our continuity of experience.

INTEGRATION

So how do you actually hear something? Not just how sound causes the ear to generate nerve impulses sent to the brain – that’s physics and physiology – but what causes you to be aware of sound, and to actually experience it?

At the most basic level the experience of hearing isn’t revealed to you as an object. In other words, when you hear music this hearing isn’t available to you as yet another object of awareness that is “like” the music. If you take that assumption to its ultimate conclusion you run into an infinite regression. Neither is your hearing simply absent; we can after all hear sounds. Rather, hearing reveals itself via sounds known through the fifth aggregate, consciousness. This aggregate is sometimes referred to as awareness. To use a grammatical metaphor, our awareness of music is an intransitive, receptive process. The same is true for the other five senses.

The experience of sound is also dependent upon conditions, such as the presence of music, previous experiences listening to music, and other mental factors, i.e., the content, and the attendant processes of the aggregates. These capture how we relate to it. The whole complex of mental processes is conjoined whereby the music impinging upon our ears will be recognized (or not), remembered, and conceptualized. Conversely, the physically and mentally presented aspects of sound are dependent upon sound consciousness for them to be experienced. Both sound consciousness and the physically and mentally presented aspects of a sound arise together, and are thus dependent upon each other; this is an example of dependent co-arising. It is the interplay of these two complementary processes that makes up the listening experience. These processes follow one another so rapidly that we believe we instantaneously hear music.

--

So what makes a piece of music ‘good’ or ‘not good’? Recall that the affective quality of music as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral embodied by the vedanas arises instantaneously, conditioned or fed by past experience. If the affective quality is pleasant we’ll grasp after the music in order to hear more, and cling to the experience in order to hear an entire song. If the affective quality is unpleasant aversion arises and we’ll reject the music by either turning it off, physically moving away from the source, choosing something else, or the like. These are actions initiated by intention that arise in response to aversion. Finally, if the music doesn’t engage us and is thereby uninteresting or neutral, our mind – which habitually seeks pleasant experiences – will wander to something else that is present: a sight, other sound(s), or thoughts. You might think of these as our reactive responses to music. Music is present and we instinctively react without giving it much if any thought at all. We notice not just the experience of music, but the experience mixed with our opinions about it. Mindfulness practice teaches us to recognize this reactivity as it happens or soon thereafter, and hear the music as just music. Or at an even more fundamental level, to hear sound as just sound.

Another source of the consonance or dissonance that drives our reactions toward music is in the interaction between how we see ourselves through our musical tastes and previous experiences, and how things actually are in the moment while we are listening. By non-judgmentally listening we are more able to see things as they truly are – just sound, just music – and not get carried away by what we hear because of dissonance (or consonance) arising between our personal conceptions of good or bad and present-moment experience. This allows us to investigate unfamiliar and possibly interesting time signatures, chordal structures, or even new musical genres, as well as plumb new depths in cherished and familiar music.

Here’s the catch: Even though we understand intellectually that we are aging, and our bodies are changing, we generally see everything else about ourselves as an unchanging continuum over time. We label ourselves as a person who is happy, or open-minded, or generous, or successful, or hands-on, or an intellectual, or an excellent musician, or someone with superb taste in music (whatever that taste may be). We tend to accept these as static attributes. We seem them as part of ‘us’, or ‘of us’. Consequently, if anyone questions our taste in music we are inclined to defend it, or even see that questioning as a personal attack. But in fact it’s merely a view that differs from our own. Our reaction arises due to fixed ideas about ourselves that we cling to colliding with other information. It’s just thoughts chasing after previous thoughts.

A more helpful perspective is seeing these attributes of our personality through the framework of the aggregates. We can investigate the elements of personality and see directly how they continually change over time, like when we are alone versus when we are with friends, or at work, with our family, or in some other setting. Each situation draws upon certain patterns of thought, speech, and action that fit in that moment, then are set aside when moving on to the next role. We manifest a variety of identities / roles throughout the day.

Not having to present to ourselves to the world as a fixed and unchanging ‘me’ frees us to experiences sound and music in that moment. We can answer the question, “What music do you like?” with “I like… music.” By holding on less tightly to “this particular music defines me” we become less prone to sparking the dissonance between how we see ourselves as a listener and how sound and music unfold; between how we see ourselves and the world and how the world actually is. And that is freeing. It opens us up to new possibilities in music, both familiar and unfamilar. It opens us up to life.

--

Another attribute of the discursive mind is mental proliferation, the waves of thoughts and concepts that ebb and flow. Thoughts are merely words, sounds, or images arising in the mind. We’ve spent a lifetime working with thoughts through the process of thinking – and we have a lot of practice! The Buddha gave an insightful analysis of thinking in a discourse called The Honeyball for each of the six senses. Here is an excerpt on hearing:

“Dependent on the ear and sound, sound-consciousness arises. The meeting of the three is contact. With contact as condition, there is feeling tone. What one feels, that one perceives. What one perceives, that one thinks about. What one perceives, that one mentally proliferates [i.e., conceptualizes and associates]. With what one has mentally proliferated as the source, perceptions and notions tinged by mental proliferations beset one with respect to past, future, and present forms cognizable through the ear.”

Once we have noticed the object (contact) we put it into a known category and label it (perception). This is largely automatic. The conceptual label along with the object’s associated affective quality can trigger a cascade of ideation and concept associations using memory, e.g., the process of thinking. We reminisce about times we’ve heard a song before, or imagine a sultry night under the stars listening to a favorite band, or speculate about why nice-sounding headphones are so expensive, or any number of things spanning the past and the future.

Most of the time that we are walking about, sitting, or standing we’re thinking about some sense experience. What the Buddha is pointing out in the Honeyball discourse is this tendency to move from direct sense experience of something into thinking about that experience, and then through conceptual proliferation (‘thought trains’) moving even further from it. Thoughts, stories, associations; lather, rinse, repeat. Somewhere buried under all those conceptual layers lies direct experience.

We’ve all experienced thought trains, which are an embodiment of mind wandering. It can be difficult to listen to music amid all that mental noise, especially if music is only cast as background, or is challenging in some way. But with practice in listening – actually paying attention to the sound and its attributes as our primary focus, without judgment, over and over – and remembering to return to what we’re listening to, over and over, with time it does get easier to actually hear music. Just the music. In this way listening to music can be a superb mindfulness practice.

Practice in careful, attendant listening is helpful because an ideal location for a wedge that can provide space before conceptual proliferation and reactivity spins up is between the vedanas and the volitional mental formations of judging, comparing, associating, ideation, and intention. Mindful listening teaches us to observe the start up of these processes, and thus let them be. They will fade of their own accord since that is their nature. A quiet and less distracted mind, trained by non-judgmental listening, is less likely to be sucked into the twin vortices of dismissing what is novel or challenging, and endless thinking.

It’s important to note here that there’s nothing wrong with thinking about music – or anything else for that matter! Our minds are very good at thinking; most of us have a few decades or more of practice. There is a place for ideation, associations, storytelling and the like. The challenge is to be aware that these processes are actually happening, and to recognize when they are useful, and when they’re just another form of distraction to fill up time. In other words, can we distinguish between the direct experience of music, and how we subsequently relate to it? More generally, can we distinguish between any direct experience and how we are relating to it?

--

APPENDIX

While this has been a lot of fun, why should you believe anything that I wrote?

This question largely hinges on the validity of the aggregates model. Fortunately, you can utilize the model in analytical meditation on sound and other phenomena, and in doing so determine their validity for yourself. Think of it as first-person science.

One way to work with the aggregate model is to ask yourself, “Is that it?” In other words, can you first identify and observe all of the functions delineated above in meditative practice or daily life? Along with this, can you observe their changing and impermanent nature? This is one of the remarkable things about meditative practice: using the mind to observe the mind. And it takes… practice.

The second way of working with the aggregates is to pose a question: Is there something missing from this functional model? And if not, what are the implications?

It’s one thing to adopt a view that frames experience using the aggregates as a template. This is just another form of practice that’s a bit more analytic than, say, meditation on the breath. It’s a far greater ask to adopt a provisional view that there is something beyond them, that there is something missing in the model, then seeing if you can negate this view. To embark on this task takes faith and trust. Faith possibly couched in the knowledge that others have taken this on and found that the aggregates are ‘the all’. And trust that you are up to the task. Fortunately, we can learn from those who came before and leverage their methods and experience.

(c) 2020-24, Shawn Burke, all rights reserved.

REFERENCES

Mark Joseph Stern, “Neural Nostalgia,” https://slate.com/technology/2014/08/musical-nostalgia-the-psychology-and-neuroscience-for-song-preference-and-the-reminiscence-bump.html

Daniel J. Levitin, This is Your Brain on Music, Penguin Books (2007).

Analayo, Satipatthana, Windhorse Publications (2003).

Evan Thompson, Waking, Dreaming, Being, Columbia University Press (2015).

Guy Armstrong, Emptiness: A Practical Guide for Meditators, Wisdom Publications (2017)

Jay L. Garfield, The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika, Oxford University Press (1995).

The Dalai Lama, The Middle Way, Wisdom Publications (2014).

Robert Wright, Why Buddhism is True, Simon & Schuster (2017).