Halley to NEOWISE

Comets—their influences upon history, society, and me.

2020 NEOWISE

The summer of 2020 was graced with the unexpected beauty of Comet NEOWISE. NEOWISE is an acronym for NASA's Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer mission, a space probe built to detect asteroids along with the occasional comet. NEOWISE discovered the comet on March 27, 2020. At first it was much like several other faint 2020 comets such as Atlas or c/2017 T2 PanSTARRS, but that began to change in June and came to full fruition in July. Because comets are named for their discoverers, this comet was named for a space probe mission, NEOWISE.

“I've been thinking a lot about Comet NEOWISE. The comet made its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) on July 3, 2020 and became a wonderful naked eye object for several weeks. This passage increased the comet's orbital period from about 4400 years to about 6700 years.

“During its last passage through the solar system (around 2400 BCE), the Egyptian Pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, had recently completed the construction of enormous pyramids in Giza.

“On Comet NEOWISE's next return (around the year 8700 CE), I wonder if the human race will still be around to see it. With unchecked population growth, accelerating environmental damage, global climate change, mass extinctions, political instability of governments, economic collapse, food shortages, and COVID-19 (and other diseases), I'm not optimistic about the future of our species.”

~Fred Espanek, July 31, 2020 on Facebook

Celestial Omens? Throughout history comets have been seen as harbingers of profound historical events. Surprisingly it seemed, whenever a comet appeared in the sky, something was always happening in society at that time. The fact that events happen all the time never seemed to occur to people because it was clear to the masses that somehow the appearance of a comet was responsible for whatever was happening in their lives, and it was usually bad.

1066 Halley’s Comet made its regular appearance (though they didn’t recognize that regularity at the time) just as the Normans were invading England. That was bad news for King Harold who was soon killed in the Battle of Hastings, and according to popular lore he was killed by an arrow in the eye, perhaps the arrow in the eye was a fitting metaphor for what happens when you see a comet. There is no real evidence he died that way, but it makes a great story. A tale immortalized in the 900 year old, 70 meter long, Bayeux Tapestry that illustrates the history of the Norman invasion.

1305 Giotto di Bondone painted the Adoration of the Magi in the Arena Chapel in Padua, Italy. The fresco clearly shows a comet above the manger signifying a celestial Star of Bethlehem, this time the omen was seen as a positive one. It is believed that Giotto was inspired by the 1301 appearance of Halley.

1857 In 19th century France the fear had been transformed into a more tangible terror as a clearer understanding of comets had changed from a celestial sword of the Gods to a celestial visitor. The comet was no longer an omen of war or pestilence, but instead the fear was of the more concrete idea of Earth being hit and destroyed by this object that moved through the solar system.

1910 Even as science was beginning to unravel the mysteries of comets, the science was twisted into irrational fear. In 1910 it was detected that arsenic was present in the tail of Halley’s Comet, combined with the discovery that Earth was going to pass through the tenuous tail, clearly trouble was at hand. Would humankind all be poisoned? Not if you bought Hopes Anti-Comet Pills!

2020 Oh, how we like to worry and live in fear. Our brains like to make connections for better or worse, usually worse. If you follow the logic of the ages shouldn’t we have a comet appear during a pandemic like Covid-19? Wait a minute, does that mean that NEOWISE is an omen? Could this summer’s comet have anything to do with Covid-19? There are those who will make this connection and believe it with a religious fervor. Such is the history of the human condition.

1973, Kahoutek—The Christmas Comet, Sebring, Florida While on a holiday trip to Florida to visit my grandmother’s brother, Uncle Phil, I searched those warm Florida skies for Comet Kahoutek. There was so much about Florida that was exotic to this 14 year old kid from Maine. It was as far from home as I had ever been. We saw palm trees, orange groves, fields of cotton and tobacco. We encountered alligators and pelicans. Disney World and Busch Gardens were exciting day excursions. It seemed only natural that this comet would be in this strange place too. The timing was perfect, its perihelion was on December 28, it was supposedly visible–they said so in the news. Uncle Phil let me use his binoculars, but I didn’t have a clue where to look, but I looked every night. I remember seeing something that was sort of fuzzy. I wasn’t sure it was the comet, but I really wanted it to be. Maybe it was, probably it wasn’t. As it turns out, I am grateful that Kahoutek was so elusive because it taught me a few important lessons. Comets, like many interesting things, require skills and knowledge to fully appreciate (and sometimes even to find). Armed with skill, knowledge and understanding, you come to know if that fuzzy object is a comet, a nebula, or a galaxy. And you’ll better appreciate whatever you are seeing. It taught me to appreciate the search, the journey, and most importantly, the subtleties.

1976, West Described as a “great comet” because it was clearly visible to the naked eye. Reaching perihelion on February 26, 1976 it was said to be bright enough to be seen during the daytime. I didn’t see it at all. My life was all about high school, friends, music, and being social. I never even heard about it at the time. Its personal importance to me is because I’ve heard so much about it since. Other comets are frequently compared to Comet West. “Did you see West? It was the best.” No, I didn’t see it. Pay attention, is the lesson here. All I have to do is say to myself “Remember Comet West” which simply means, “Pay attention.”

1985, Hartley-Good, Mapleton, Maine My friend Wayne Madea had an observatory in his backyard with a C-8 (Celestron 8” schmidt-cassegrain telescope) inside. He found this faint comet for me to see. No tail, just a faint object that looked like a star that someone tried to erase with a bad eraser. We knew Halley’s Comet was coming soon, so it felt good to see a comet before the famous one came along.

Fall 1985,

Halley, Aroostook County, Maine

I had been working and teaching in planetariums since 1979 when I was the student director of the University of Maine Planetarium. In the autumn of 1983 I moved to northern Maine to become the director of the Francis Malcolm Science Center Planetarium upon its opening that fall. Two years later, in the fall of 1985, I found myself as the county’s expert on comets. The planetarium was the center of astronomy education in Aroostook County (which is locally known as simply “The County”), and since the planetarium was basically a one-man operation, that meant I was the local expert.

The New Local Expert

The local TV station wanted an interview, there was a newspaper reporter who wanted to interview me. Could I speak to the Rotary, the Kawanas, the Lion’s Club? I had to study up a bit to expand my cursory understanding of comets, and I had to do it quickly. Luckily, it was a fascinating assignment. The interviews and speaking engagements went fine. The people of The County were curious and wanted to know more. They wanted to see this famous sky wanderer and I was expected to be their guide. I realized that I had to get it right and I had to step up and help people learn to see, to understand, and to be inspired. When I thought about it, that is exactly what I loved about teaching in the planetarium, and now more than ever the public and students of The County were actively seeking it out.

Comet Halley—Once in a Lifetime

Sharing the comet beneath the planetarium dome

I ordered two planetarium show kits about Halley’s Comet, one from the Hansen Planetarium (now the Clark Planetarium) in Salt Lake City and one from the Science Museum of Virginia’s Planetarium in Richmond. Canned or pre-recorded planetarium shows at the time consisted of a soundtrack recorded on reel-to-reel 1/4” tape, a script, and a set of several hundred Ektachrome slides, along with instructions about building and/or using appropriate special effect projectors. It was then the planetarium staff’s job (my job) to adapt that canned show to fit your own star theater with its own particular strengths and weaknesses.

The challenge was to make this pre-recorded show work within our 24’ tilted dome which featured 12 Ektagraphic III slide projectors and about 20 special effect projectors along with our Spitz Nova star projector. Everything was operated manually from our console which consisted of remote slide projector controls, dimmers, on-off switches and a 12 volt system for small motors and special effects lamps. This was before computerization and digital projectors, at least in domes with as small a budget as mine. I masked slides with opaquing ink and mylar tape and mounted them in glass Wess mounts. We built special effects with small motors, baby food jars and glass pepsi bottles (remember how the glass of those Pepsi bottles had swirl pattern, great for a nebula effect), flashlight bulbs, old film-strip projectors, and if we got ambitious perhaps a helium-neon laser. To make a long story short, I combined the two shows into one and it became one of our most popular public presentations ever.

I also developed a live interactive planetarium show for school groups so it could be tailored for different ages and learning styles. Comet Halley became the primary focus of almost all the planetarium shows that winter and spring.

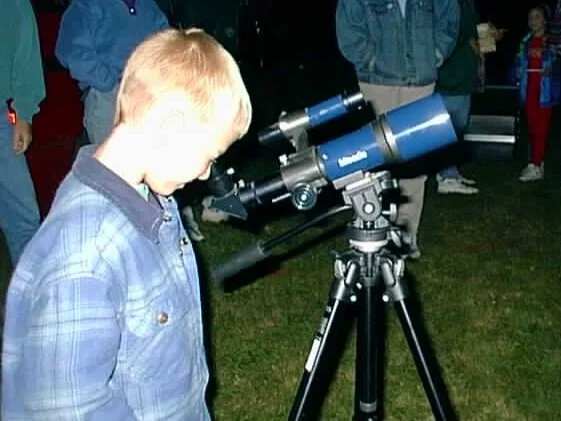

Public viewing of Comet Halley

We had a several telescopes at the Science Center and we used them for comet viewing after every planetarium show when the skies were clear. I remember this one potato farmer from Washburn looked at the comet through the telescope, “That’s it?” he asked, “I drove 35 miles to see a smudge of light?” “I’m afraid so,” I answered, “come back next week, it might be brighter and we might see a tail developing,” With a wry smile he replied “I’ll think about it,” as he gathered his daughter and headed out. I thought I’d seen the end of that family. But I was wrong.

They came back every week with their expectations in check, and that same potato farmer started noticing small changes in the comet’s appearance. And I think he saw that his daughter was sincerely interested and excited about the comet and the night sky, and that was something he valued. I admired his curiosity and the fact that he wanted his daughter to love science.

I met two local people who remembered seeing Comet Halley in 1910. C. Hazen Stetson of Presque Isle and Clara Anderson of Fort Fairfield. Mr Stetson met with me and told his story, but was a private gentleman who didn’t want time in the public eye. Clara, on the other hand, had seen the comet in 1910 as a young girl living in The County. She wanted to see it again. “It was better in 1910, but it’s good to see it again,” she quipped as she pulled her eye away from the telescope. Then she went into the Science Center. We got her a comfortable chair, and she told her story about seeing Halley’s Comet in 1910 to anyone who would listen. She told her tale over and over and over. When I asked if she was tired and wanted a ride home, “Why no, I’m having a wonderful time with all these youngsters.”

Cometary orbits tend to be highly elliptical with t

he tail longest when it’s closest to the Sun.

In January 1986 Comet Halley disappeared behind the Sun. If Earth had been at a different spot in its orbit so we could have seen it when the comet was at perihelion, the tail would have been impressive indeed, much like Clara remembered from 1910. It reappeared from behind Sol in March. The comet was supposed to be a bit brighter, but the apparition would no longer be in the evening sky, it would be in the early pre-dawn skies. On the new Moon that month we held our “Hard-core Halley Watch” starting at 3 AM. Clara was the first to sign up, she wanted to be there. So I picked her up at 2:30 that morning. She took her look at the comet through the telescope, then went inside to her comfy chair and told her story numerous times until the Sun peaked over the spruces at the edge of the field across the road.. Over 100 people showed up for the event and everyone was excited to see their favorite smudge in the sky one more time.

April 1986, Halley, Uluru, Australia Joining Amateur Astronomers Inc. I travelled with friends to central Australia and observed Comet Halley from the base of Uluru (aka Ayers Rock) just south of Alice Springs, Northern Territories. The southern skies were amazing to see. An new sky with new constellations. Even the constellations towards the north, which I knew well, seemed different as they were all upside-down. The comet was visible to the unaided eye and the tail was simply an elongated smudge, but it was a fine sight in binoculars and even better in the telescopes some of the other amateur astronomers had brought along. After a couple of hours of observing the southern skies, someone said with slight irritation in their voice, “Who’s got their flashlight on?” It turns out no one had their flashlight on, the shadows we had all noticed were our own caused by starlight. None of us had ever seen a sky as translucent and clear with stars as bright. Halley’s Comet had led me to the opposite side of the globe, visiting Hawaiian volcanoes along the way, Queensland rain forests, the world class observatories at Siding Springs, and the radio telescope at Parkes, as well as the chance to see wild kangaroos and koalas, emus and kookaburras, visit the outback, and attend two different performances at the Sydney Opera House. That dirty snowball helped expand my world again, well beyond the orange groves of sunny Florida and my beloved coast of Maine.

1986-1992, Thiele, Bradford, Liller 1988a, Okazaki-Levy-Rudenko, Austin, Levy 1990C, Swift-Tuttle These are some of the comets I saw during this time. Several of them were viewed numerous times. All were basically telescopic with no discernible tails as seen through my newly acquired C-8 telescope that I bought after Halley had left the building, leaving a glut of telescopes to go on sale. None of these comets were extra-ordinary in any way, but they helped me to hone my skills with the telescope as some of them were quite difficult to locate. There were no GoTo telescopes back then, at least within my budget. It was good practice that taught me a lot about the telescopic sky, and the search was always rewarding, even if each comet was nothing more than a faint smudge of light.

1994, Shoemaker-Levy 9 hits Jupiter

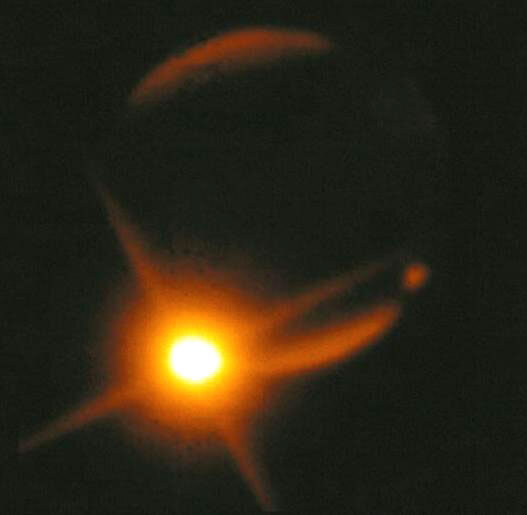

Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 broken into 20+ pieces by Jupiter’s gravitational stresses in 1992.

Photo credits: Hubble Space Telescope Comet Team and NASA / Public domain.

I never saw this comet, but I talked about it a lot under the planetarium dome. In July 1994 Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 crashed into Jupiter creating large dark spots where the more than 20 pieces to this comet exploded upon impact. It was in pieces as a result of passing too close to Jupiter two years earlier. The giant planet’s gravitational forces tore it apart. In 1994 the pieces collided one after another into Jupiter. The largest impact site occurred on July 18 when fragment G struck Jupiter. The dark spot created by the G fragment measured over 7,500 miles across, and was estimated to have released an energy equivalent to 6,000,000 megatons of TNT, that’s 600 times the world's nuclear arsenal at the time.

Photo courtesy of Max Planck Institute for Astronomy / Public domain.

The explosions happened just around the limb of the planet, but as Jupiter rotated the impact sites came into view and appeared as dark spots. These scars could more readily be observed and lasted for several months after the event. This image was taken with the Hubble Space Telescope.

It was a huge news item. Could a comet hit Earth? Yes. Is a comet likely to hit Earth soon? No. How can dirty snowballs make such big explosions? Speed and size. Can we see the explosions with our eyes? No. Are there pictures? Yes. And why is it number 9 when there were 20 pieces? It was the ninth comet that Eugene Shoemaker and David Levy had found together. And so the questions went . . . .

Photo credits: Hubble Space Telescope Comet Team and NASA / Public domain.

1996,

Hyakutake, Fairfield, Maine

This was my first sighting of comet with a long, clearly visible tail. This was the best comet I had ever seen at that point in my life. After the smudge of Comet Halley, Hyakutake had a visible tail that I measured as 17° long. The first time I saw it the comet was telescopic, little more than the familiar expected smudge, much like the earlier comets I had seen. The tail was supposed to be visible, but it was low in the northeastern sky. If I wanted any hope of spying the tail I would have to get up at 3:30 a.m. when it would be near the zenith. So I set my alarm for 3:30 on the morning of March 24, 1996.

It took me a bit of time to drag myself out of bed, but by 4 a.m. I was dressed and I headed out to the neighbors open yard where I looked up. The comet’s tail stretched across the zenith overhead! I woke up almost instantly, it had caught my attention! I ran in, woke up my wife and kids to bring them outside to see this amazing sight. We spread a blanket out on the ground, laid down in the dark to gaze upon this hairy star. We were awe-struck when out of the darkness the neighbor’s cat joined the party and sprayed us as we lay upon the ground. That rapidly changed the mood!

1996-97, Hale-Bopp After the amazing appearance of Hyakutake that spring, I had assumed that I had seen the best comet of my life. Then in August Comet Hale-Bopp arrived. At first it was another telescopic comet, but soon became visible to the unaided eye. Then after it passed perihelion in the spring of 1997 its brightness exceeded all expectations. This comet outshone even Hyakutake. I never saw a tail quite as long as Hyakutake, but Hale-Bopp had a very distinct and bright tail. The entire comet was not subtle in any way. If you went outside and looked up, you could not miss seeing this wonderful comet. We observed it for nearly a year with a combination of the unaided eye, binoculars, and various telescopes. I took photos of it and shared viewing it with everyone I could find. Hale-Bopp was everything I had wanted Halley to be. It was what everyone expected Comet Halley to be. It received a lot of attention from the astronomical community, but it never quite reached the public hype of the famous Halley, much to my dismay.

Ben and Emily, my two oldest kids, observing Comet Hale-Bopp in the spring of 1997.

1999-2006,

Wild 2

In 1999 the Stardust Probe was launched and in 2004 it flew through the tail of Comet Wild 2 collecting particles in a sheet of exposed aerogel—one of the lowest density and lightest solid materials known, looking much like clear Jello, but with a consistency more like firm styrofoam. Here we see particles embedded in the aerogel. Once the passage through the tail was complete, the aerogel was covered to protect the contents from interplanetary contamination, then the probe returned the collection of tiny particles back to Earth in 2006 to be examined.

Photo credit: NASA/JPL Stardust Mission, 2006.

A comet’s tail has two parts, a dust tail which is wide and bright, and a more thin and tenuous ion tail. Remember that comets are essentially dirty icy snowballs orbiting the Sun. As they approach perihelion the ice and snow sublimates to a gas, the solar wind pushes the gas away from the Sun creating the tail, the gases become ionized as electrons are stripped away. As the snow sublimates it releases dust particles to create the dust tail which also mostly points away from the Sun, but it also leaves material behind so it often swings off to the side a bit, separating it from the ion tail. In any case, both tails are tenuous at best, as cometary astronomers like to say, “A comet’s tail is as close to nothing as something can be and still be something.” Well, Stardust caught a piece of tail and brought it home.

2004-2012, NEAR, Macholtz, Holmes, Lulin, Hartley 2, and Garradd The early 21st century saw a string of faint comets. None of them were enough to excite the public. None of them made it into any of my planetarium shows beyond a cursory discussion during a star point-out. None of them were exciting. Yet, this is a list of the ones that I searched out and successfully found multiple times. There were others, such as Tuttle in 2008 that I only spied once, never to see again either because of clouds, the Moon, or it was simply elusive. There is something about these faint wanderers that draws me. Some are short period comets that orbit the sun in small orbits with regularity, but many are long period comets that come in from the Oort Cloud, pass perihelion and head out not to return for tens of thousands of years, if ever. One might think that these snowballs are wandering somewhat aimlessly through the outer reaches of the solar system, but that would be as wrong as believing a comet is a harbinger of evil on Earth. Even these long distant travelers that so infrequently let themselves be known to us are controlled by the mechanics of gravity, their mass, and momentum. When we feel like our lives are controlled by forces greater than ourselves, we often attribute it to God or some higher power, but I think that higher power is simply the mechanics of the universe, perhaps on a scale that some fear to contemplate. Others marvel in that scale and complexity, exploring it with patience, knowledge, logic, and science, in so doing, we can begin to unravel the mystery. These dirty snowballs flying through space remind me of that.

2013, PanSTARRS C/2011 PanSTARRS was the best comet since Hale Bopp, a subtle comet that was faintly visible from a dark spot with the naked eye. It had a nice tail and I photographed it numerous times in the spring of 2013. I spent some very cold late winter evenings near the frozen frog pond at the Goodwill-Hinckley School Farm. The comet was low in the northwestern sky just after sunset which made for a nice colorful photographic composition. The shot of it over the barn, set against the harsh flood lamp gives you a sense of its intensity and visibility despite the local light pollution.

2013, ISON, and Lovejoy C/2013 Observations became more intense for me around these two comets. This duo marked the last month of my mother’s life. No, they didn’t cause my mom to die, they simply were traversing the inner solar system during that time of her life. These comets served me as an intriguing set of objects to focus on visually, photographically, and intellectually, giving me a focus that had nothing to do with my mom. My wife Laura, my sister, and I were providing end of life care which is nearly all consuming, especially when it’s someone you love. My doctor told me that I needed to take time away from her if I were really going to be there for her, otherwise this type of care can take a severe toll on the caregivers. These two comets were part of my personal care from the 24 hour care that the three of us were performing for mom.

ISON was promising to be another Christmas Comet. ISON was a sun-grazing comet, which simply means its orbit carries it very close to the Sun. Such comets, if they survive close passage, often have spectacularly long tails. ISON reached perihelion on November 28, Thanksgiving Day here in the U.S., and its orbit was aligned with Earth’s orbit for a spectacular show in December. In the back of my head I envisioned it as a celebration of my mom’s life at the time of her passing. Mark Twain said in 1909, I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year (1910), and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: "Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together." My mom didn’t come in with ISON and no one would call her a freak, but it felt right that perhaps a spectacular comet would be a fitting farewell. However, ISON was destroyed by it's close approach on Thanksgiving, there would be no show for me, my mom or anyone else. Mom passed away on December 16, there was no Great Comet marking the event. It was a quiet mundane Monday evening, and in the end that was probably more appropriate.

Lovejoy c/2013

This fine comet was visible at the same time as ISON, just barely reaching visible eye magnitude if you knew where and how to see such things. After ISON, which the media had highly promoted only to see it dissolve away by the forces of the solar wind, no one was going to promote a comet that had no hope of being bright. Lovejoy c/2013 quietly made it round the buoy of the Sun and then faded away as it withdrew.

The last time I saw Lovejoy c/2013 was on December 14, two days before my mom’s passing. Looking for the metaphor I wanted from ISON, this comet in the end was more appropriate for Mom who wasn’t showy or anyone to call attention to herself. I said Godspeed to them both in mid-December.

Comet

Lovejoy C/2014 Q2

Comet’s, as I pointed out earlier, are named for their discoverers. Here we see another comet discovered by Terry Lovejoy, a distinguished astro-photographer who has discovered six comets as of 2020. While my cometary photography pales compared to his, this is my image of Lovejoy c/2014 Q2 passing by the Pleiades with a tail that I couldn’t see with my eyes, but came through in the photograph.

2014 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko

The Rosetta Probe reached Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in May 2014, went into orbit about the nucleus of the comet in August, and in November soft-landed (sort of) the Philae Lander on the surface of the nucleus. Rosetta gave us the most detailed images of a comet’s nucleus ever taken. Boulders, cliffs, and jets of sublimating ices were photographed in detail. Analysis of the water composition found the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in the water from the comet to be three times that found for terrestrial water which suggests that Earth’s oceans were not derived from comets such as this one.

The Philae Lander bounced twice upon landing before finally settling in a shadowed area beneath a cliff face. Without solar power the probe only operated for 2-3 days.

Artists rendering of Rosetta, Philae, and the comet courtesy of: European Space Agency / CC BY-SA 3.0-IGO (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0-igo)

Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko showing a sublimating jet shooting out toward the Sun. Photo credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 / CC BY-SA 3.0-IGO (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0-igo)

2015-18 Catalina, Johnson, Giacobini-Zinner, Atlas, and c/2017 T2 PanSTARRS, More faint comets, some barely visible, the challenge being simply to find them, look upon their light, and contemplate their stories. Two of these celestial snowballs provided interesting passages near deep space objects, one of which I photographed while the other I sketched.

2018 Wirtanen, a bold comet in many ways. No huge tail, but a distinctly green coloration which drew me in. Then in December 2018 it passed between the Hyades and the Pleiades Star Clusters making a fine sight in binoculars and a challenge to photograph.

The Hyades in the upper left, Comet Wirtanen, and the Pleiades on the right.

2020

c/2017 T2 PanSTARRS

Comet c/2017 T2 PanSTARRS passed near the galaxies M-81 and M-82 in Ursa Major. Always a fine sight, these two galaxies are favorites for many amateur observers. For a couple of days in May 2020 there appeared to be three, but in reality the third was a much much closer and much much smaller solar system object.

I like these conjunctions of sky objects because they illustrate that while in a telescope they look much the same, it’s through the works of astronomers and scientists such as Edmund Halley, Johannes Kepler, William Hereschel, Joseph Fraunhofer, Robert Kirchhoff, Edwin Hubble, Fred Whipple, and Carl Sagan, among many others, that we have discovered that there’s more to these smudges than meets the eye. Interestingly, the Messier Catalogue of objects arose to distinguish deep sky objects (galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae) from the comets that Charles Messier was looking for in the 18th century. I thank these scientists for their contributions so that we have a better understanding today. This is the true intersection between human events and comets, perhaps an omen of further and deeper understanding to come.

c/2020 F3 NEOWISE

In July I was doing photography for the Maine International Film Festival. The entire festival was being held at the Skowhegan Drive-In due to the current Covid-19 pandemic. It was an interesting festival to shoot, everything happened outdoors, everyone was wearing masks and doing their best to practice social distancing. Since Covid had first hit in mid-March there had been several faint comets in the skies overhead, all so dim they all required a telescope to see. Within the astronomical community a prediction arose that the latest of these comets, Comet NEOWISE, promised to become bright and visible to the unaided eye. That would an exciting development. Perhaps I could a get a photo of the comet in the context of the film festival?

After spending the past 40 years observing the sky and chasing comets, I have learned to take such predictions with a grain of salt. Seldom do the predictions of brightness prove true, although we all secretly hope that this might be the one. Someone joked about it saying, “Of course this one will get bright, there’s a pandemic going on!” referring to the historical social connection between comets with famines, war, and pestilence. We laughed, and of course it came true. Comet NEOWISE became the brightest comet since Hale-Bopp in 1997. Unlike bright comets of the past, despite the coincidence of its appearance during Covid-19, I didn’t hear many folks fearing what the comet means, instead, I heard lots of people talk about the comet as a welcome gift, a diversion that we can all enjoy during such a difficult year. That alone gives me great hope.

I hosted a star party (sans telescopes) at Quarry Road Recreation Area in Waterville for the local arts group Waterville Creates! in association with the film festival. We had a delightful night out, exploring the stars and constellations with a group of a couple dozen people. During the early part of the evening NEOWISE graced the sky until it set around 11 pm. I got a chance to share that rare sight with many. Interestingly, no one was frightened by it or worried about what it meant, instead people asked science questions: What is it? How does it moves? Where did it come from? How do we know that? People were in awe of the comet and, perhaps more importantly, they were in awe of how we were able to figure out so much about it. No one questioned the truth behind the science, the questions were all questions that helped them understand the science. I like that a lot, my hope grows with the promise of growing knowledge and understanding.

So I leave this meandering blog with a sense of growth, in me and hope for society. With that, I’ll leave you with a gallery of images of NEOWISE for your perusal. I have followed comets my entire adult life and have learned from each of them, not always anything profound, but always another step forward. I have tried my best to pass that forward as I go. I’ve learned to watch these snowballs flying through space, each time I see one I try to pay attention, because like the snowballs you threw as a kid, when you don’t pay attention is when you get clobbered. It’s not that you should pay attention because of fear of being hit, but because it’s part of what’s happening. We live in this universe, there are many things to pay attention to, we all choose where to place our focus, once we do that, we need to learn from it and to be with it. Moments come and go, but the one that matters the most is the one you’re in now. Be present in the moment, because if you place your focus in the right place the show is often too good to miss.

2020 Postscript Laura pointed out that readers might wonder how I remember all those comets and so much minutia about them. She has always been amazed by the fact that from my first cometary observation I’ve kept a observational diary, noting not just each comet I saw, but each observation I saw with only one exception—Hale-Bopp, because it became, for awhile, as common a sight as the Moon. At the time of my first observation of Harley-Good in 1985 with Wayne Madea, I had just acquired Will Tirion’s Sky Atlas 2000.0 Deluxe Edition. I loved it and still do. It was there that I started recording all my cometary observations and without that work, this blog would not have been possible.

My comet diary is kept on the back of each chart, depending on where in the sky I observed the comet at the time.