Thoughts on Walking

Photography by John Meader

Bom Caminho from the bridge in Ponte de Lima, Portugal

Walking is the simplest of things. One foot in front of the other, repeat.

I’m not talking about hiking. I’ve done that and it has its challenges and rewards. Here I’m talking about walking, maybe all day, or at least for a chunk of the day. Maybe for days on end. When you just walk you see things differently. Walking near home shows you things about your neighbors and the nature of the place you live. But walking in a new place allows you time to see nuances in a new place that you miss in an automobile. In any case, you get to know yourself and the world in which you live. You also get to know your feet, your legs, your cardiovascular system, and your lungs. You come to appreciate dirt roads. There can be a meditative aspect to it, and there can be a gregariousness that comes with meeting other walkers, sharing a moment with a fellow pilgrim.

Walking lends itself to seeing, hearing, and smelling. But above all, it entices my creative muse, which encourages me to share my thoughts about walking.

“The end of a melody is not its goal: but nonetheless, had the melody not reached its end, it would not have reached its goal either. A parable.”

Part 1. Hiking

I hated hiking when I was in high school and college. I liked the idea of it, I liked being on top of mountains, but I didn’t enjoy climbing. Maybe I was a bit lazy, but not really. It was more about my psychology of hiking and why I was doing it. I had to learn that the journey was more important than the goal. It required learning to slow down in a world that taught you to go fast. It was learning how to hike differently than I thought I was supposed to. Hiking had been about huffing and puffing, pushing yourself to get to the top of the mountain as fast as you could so you could . . . what? See the view sooner?

Lesson #1 Tumbledown Mountain

The pond on Tumbledown Mountain.

I remember climbing Tumbledown Mountain in Weld, Maine, with my friend Wayne Barber. We worked hard to get up that relatively benign mountain (to our credit, as I remember it, we were both carrying children in baby backpacks). When we finally reached the summit, I remember Wayne saying, “You know, just west of here there’s a great view that you can drive to, and it’s way better than this one.” And he was right. It was an enlightening moment, not because I would rather drive up a mountain than walk up one, but because it made me question why I needed to hike when I could drive. I knew that there was a value in hiking that was inherently different than a scenic turnout along a highway. But what was it, really?

Bragging rights are part of it, if I’m honest. It boosts the ego to be able to claim you’ve climbed Mt. Horrible. Even better if you did it in the rain or a driving snowstorm! This sounds egotistical, and I guess it is. But as someone who has been a collector my entire life (stamps, coins, shells, rocks, nails, books, LPs, Matchbox cars, postcards, and bottle caps—I could go on . . .) peak-bagging is a natural progression. While there is a vanity in collecting, it’s not always about bragging. It’s sometimes just about completing the set, even if no one else knows or cares. Take it as you will, maybe collecting mountain peaks is egotistical or compulsive, but it’s also enjoyable if it doesn’t become all-consuming. Though, in the end, it’s not why I walk.

Lesson #2 Traveler Mountain

Hiking didn’t become an enjoyable pastime until I was 30, though age had little to do with it.

In the summer of 1989 I met up with Shawn Burke, my collaborator on Welos Arts and Sciences, and his wife, Monica, for a camping trip to South Branch Pond in Baxter State Park. I was there with my first wife, who was pregnant at the time, and our 16-month-old son, Ben. We weren’t really there to hike, but the first morning Shawn and I decided to hike up the North Traveler Mountain trail far enough to get a view over the pond. Shawn had done way more hiking than I had.

I started off at my usual fast pace, huffing and puffing, while Shawn lagged behind. Finally, I had to stop to catch my breath—and give Shawn time to catch up. When he did, he wasn’t huffing or puffing; in fact, he was able to hold a conversation and didn’t really need a break. What the ____? When he saw how hard I was working, he suggested that if I slowed down and took smaller steps I might get less winded. He said that three smaller steps around a big rock was more efficient than one big step over it. And when you go a bit slower you see more, you can hold a conversation while you hike, and besides, what’s the hurry? So I slowed down, and it made a huge difference.

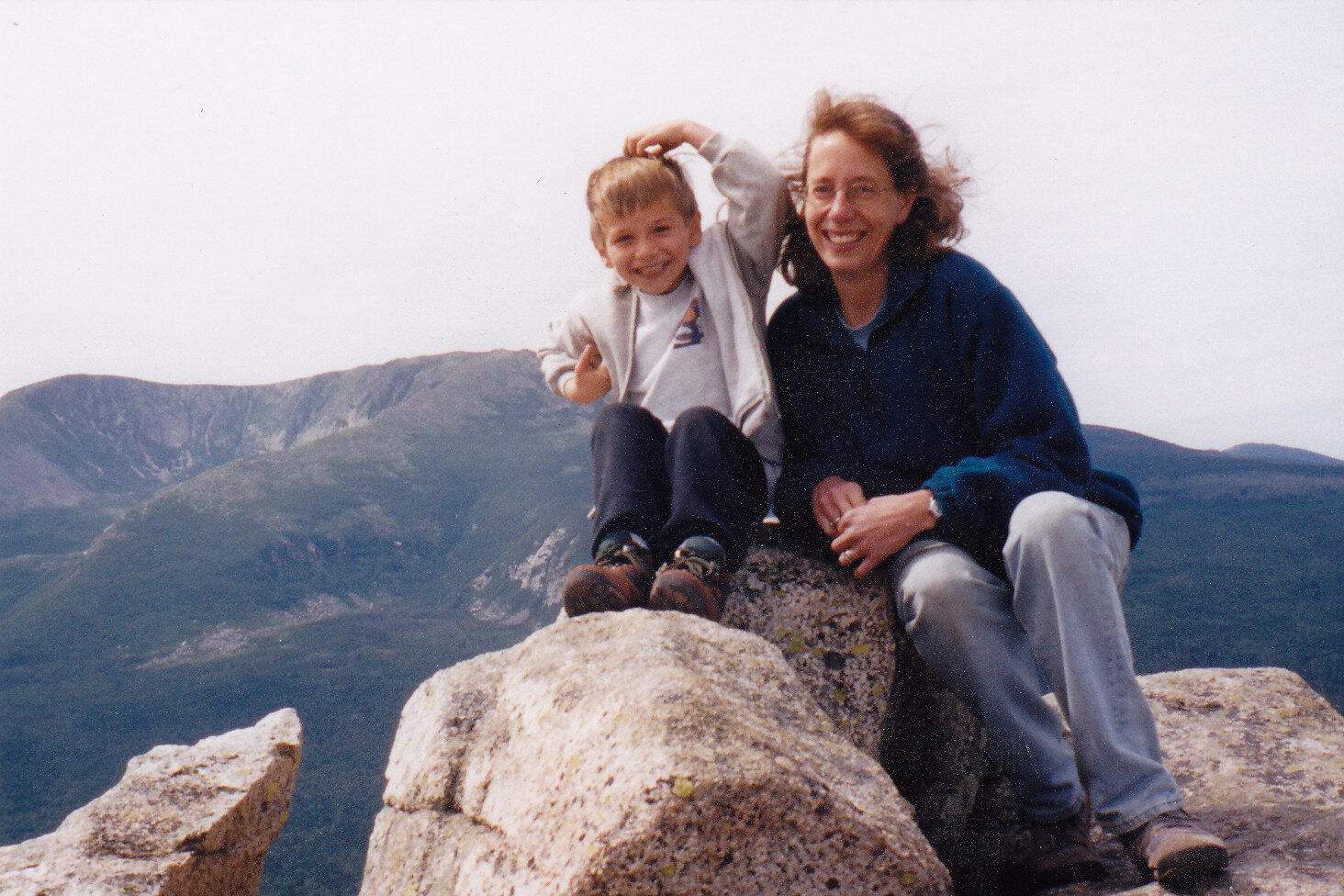

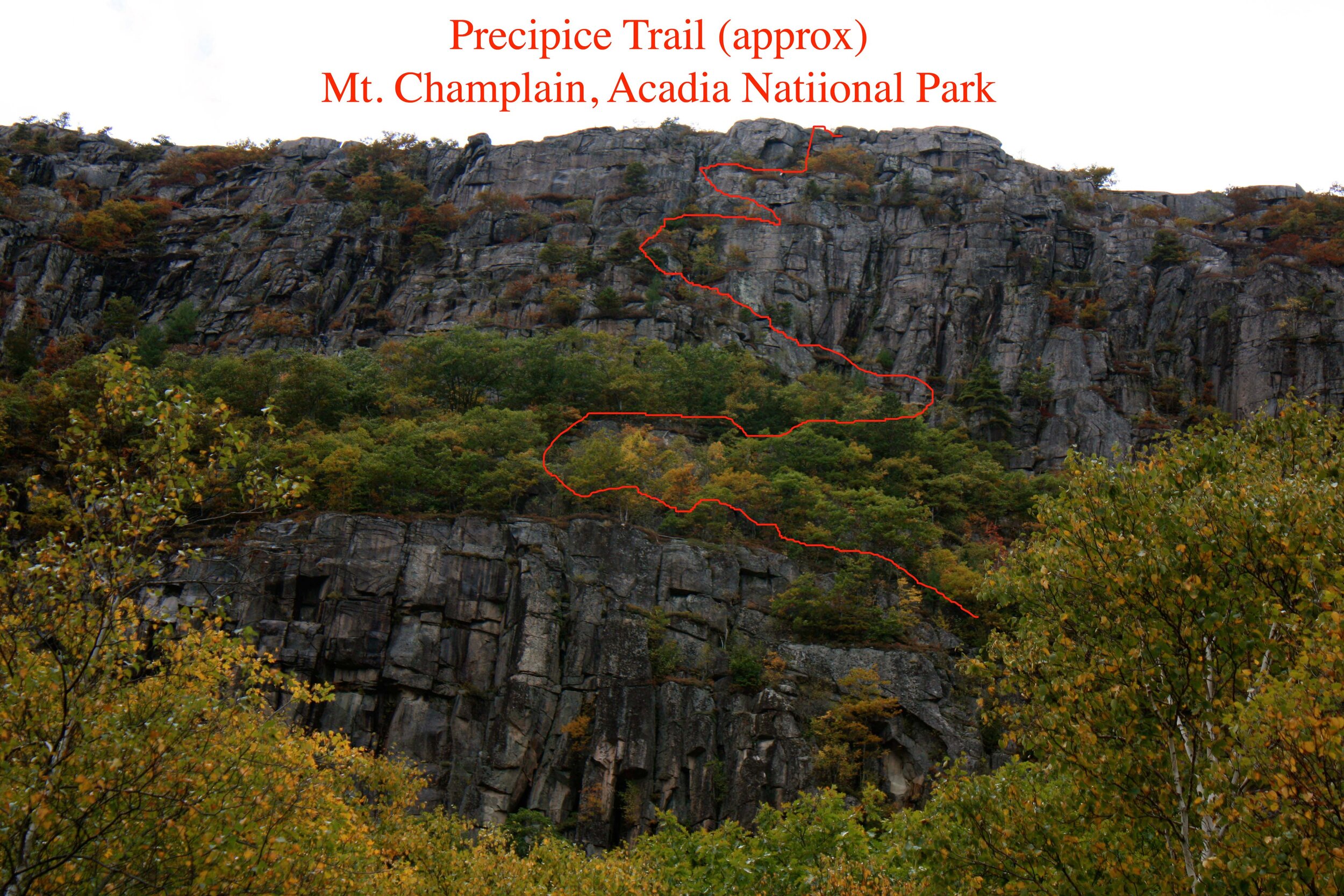

Lesson #3 Longfellow Mountains

This led to years of hiking the mountains of Maine, collectively known as the Longfellow Mountains—from the Bigelows to Old Speck, Cadillac to Champlain, Jackson to Mt. Blue, Whitecap and Kineo, and Doubletop and the Brothers and. . . the list goes on. My usual hiking partners were my wife, Laura, and my son Forrest. I learned that it matters who you hike with. Pace matters climbing mountains. I had developed a somewhat slow and steady pace as seeded by my friend Shawn on the slopes of North Traveler. It worked for me—it made hiking enjoyable and that’s important. I hiked with a few friends who all but ran up mountains, but I don’t enjoy hiking that way, so we don’t hike together anymore. Luckily, Laura had an approach similar to mine, partly because of an old knee injury and partly because we are partners and enjoyed hiking together. Forrest was young so he just learned to hike the way we hiked. We made a great trio, and we climbed a lot of mountains, sometimes all together but also in pairs.

Lesson #4 Guys’ Trips to the Whites and the Greens

Summer Trips—For several years, there were annual trips with Shawn and and my older son, Ben, to New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Summer hikes up Mounts Jackson, Eisenhower, and Liberty were combined with an annual Allman Brothers Band concert in Gilford. We even ventured into the Green Mountains of Vermont while Ben was a student at Middlebury College for a trek up the distinctive Camel’s Hump. Another hiking trio had formed. These trips were different not because we were doing anything more dramatic or physically challenging, but being three guys, we had an edgier social dynamic and looked at hiking a bit more aggressively.

Winter Trips—During winter trips, we pushed ourselves differently than we would in the summer. Winter hikes into the back country of Zealand, the Pemigiwassett Wilderness, the Great Basin, and along Vermont’s Long Trail were strenuous in an entirely different way. Winter camping in sub-freezing and often sub-zero temps requires the right gear, paying attention to procedure, and having lots of patience. Everything takes longer in the winter, and the cold is unrelenting. Having companions you trust is key, along with developing an attitude of being comfortable with being somewhat uncomfortable. And shot of scotch doesn’t hurt at the end of the day.

Lesson #5 Bushwhacking

Forrest had been too young to take part in the winter forays into the Whites and Greens, but he wanted to step into the challenge of the Guys’ Trips. So Fo and I took on a bushwhacking trip to Maine’s Saddleback Wind Mountain, which required using map and compass skills. We drove to Weld and climbed Bald Mountain, an easy hike with great views. From there it’s a bushwhack down the backside, across the col, and up the wooded slopes of Saddleback Wind. Fo loved it because there was no trail—what kid doesn’t like an adventure like that? It was definitely a Guys’ Trip.

Lesson #6 Katahdin

Katahdin—”The Greatest Mountain.” And in Maine it surely is. There is nothing like it. The exposure of its Knife Edge trail provides almost a bird-like perspective with air all around you, except under your feet. Surely, hiking from Pamola to Baxter Peak is the most spectacular mile in Maine. Of course, it’s not for everyone. At times it’s just wide enough to scramble across it with 1,000 feet drop-offs on each side. Not a place to be if you suffer acrophobia. On the other hand, the views are spectacular, and when you make your way amongst the boulders and cliffs it’ll force you to redefine what it means to be alive. I’ve climbed Katahdin six times, crossed the Knife Edge three times. Each time on different trails and with different sets of companions. It’s a mountain that all Mainer’s who hike need to experience.

Crossing Katahdin’s “Tablelands” always makes me think of Donn Fendler, who got separated from his companions as a young boy in 1939 and spent nine days alone “Lost on a Mountain in Maine.” I had the pleasure of meeting Donn a couple of times before he passed away in 2016. I listened to him share his story with school children, and I watched the twinkle in his eyes as he answered their myriad questions. His misadventure became a key part of his life story, and he shared it over and over. While I don’t wish to suffer Donn’s childhood ordeal, listening to Donn I realized that my time on Katahdin and in the Maine woods comprises an important part of my life story as well. It became important to share it with my children. When Ben and I took Emily to Chimney Pond with the idea of hiking up to Baxter Peak, she wasn’t sure she was up for it. As we ate lunch by the glacial tarn nestled into the arms of Katahdin, she saw hikers climbing up the Cathedral Trail—Baxter’s steepest trail. “Could we give that a try?” she asked. We made it to Baxter Peak, across the Knife Edge to Pamola and back down the Helon Taylor Trail to end a fantastic day.

Lesson #7 Changes

Laura and I hiked together until her deteriorating knee injury stopped her from hiking. Eventually Forrest went off to college, and the Allman Brothers disbanded, which led to fewer trips to the Whites with Ben and Shawn. I hiked alone for a while. Ben and I played with the idea of backpacking Vermont’s Long Trail. As a warm up, we took a backpacking trip through Maine’s western mountains. But we encountered Mahoosuc Notch in the rain, which left a sour taste in our mouths for backpacking, even though the notch was incredible place. We decided that canoe camping was way easier than backpacking if you just want to get out in the wilds.

Backpacking the Mahoosucs with Ben in the fog and rain, through Mahoosuc Notch— “the toughest mile on the Appalachian Trail.”

Lesson #8 The Horn and the Horizon

In August 2009 I did a solo day hike up Saddleback Mountain and the Horn, two 4,000 footers in western Maine. It was just a day or two after my mentor and dear friend, Sandy Ives, had passed away. Sandy had given me so much. He was my college professor who helped me see my own value as a student, a historian, and a human being. He helped me explore the life of my grandfather, Dell Turner, through the medium of oral history. After a couple classes and an independent study, it culminated into my writing a small biography titled Dell Turner, The Stories of His Life published by the Maine Folklife Center at the University of Maine in 1988. He helped me with one of the first great losses in my life—the passing of Grampy Turner. Now, on a mountaintop in western Maine, I looked out over vistas of lakes and mountains, and I contemplated the passing of Sandy. I summited Saddleback first, then followed the AT to the Horn, where I sat for a long time alone, starring at the hazy horizon—the vague boundary between earth and sky. It felt like a metaphor for the line between life and death, a line that Sandy had just crossed. Soon, I would care for my own mother as she prepared to cross that fuzzy line. I’ve thought a lot about that line since. One day, we all meet the horizon and step across.

Solo on the Horn.

“It is of no use to direct our steps to the woods if they do not carry us thither. I am alarmed when it happens that I have walked a mile into the woods bodily, without getting there in spirit. . . . But it sometimes happens that I cannot easily shake off the village. The thought of some work will run in my head and I am not where my body is—I am out of my senses. What business have I in the woods if I am thinking of something out of the woods?”

Part 2. Walking

So what’s the difference between hiking and walking? That’s a difficult question to answer.

Hiking is walking, but you carry different things in your head, or at least I do. When I walk, I often have a pack on my back with many of the same items I take hiking: a raincoat and polar fleece jacket, a first-aid kit, and extra socks, bug dope, and sunscreen. I have food, water, perhaps a map and compass, and definitely my camera. Sometimes my walks are longer than my hikes. Usually, my walks are not about climbing mountains or reaching a summit. That’s not to say there are no hills or elevation changes. They are about walking and noticing. It takes a while to start to notice.

So when did hiking turn into walking? I credit Shawn for this transition. Sometime in the past 10 years or so, he and Monica started taking walking tours in the U.K.—along Hadrian’s Wall, the Thames Path, the Ridgeway Trail, and others. Shawn suggested that Laura and I join them for one of these walks. It wasn’t backpacking or camping, just walking with a daypack, staying in B&Bs, and having your luggage transported for you. Dinners are either in the lodgings or at local pubs. There’s also good beer, hard cider, and scotch. And the English countryside is lovely. We were intrigued, and although Laura knew her knee wouldn’t allow for such a trip, she encouraged me to join them sometime. The seed was planted.

When I first started to consider taking longer walks, I worked at getting in the correct shape and mindset by taking longer and longer walks around town. Eventually, I found a nice training loop. From our home in Fairfield, I’d walk to Waterville, about 3-4 miles depending on the route. Once in Waterville, I crossed the Two Cent Bridge—a suspension footbridge over the Kennebec River that once charged millworkers two cents to cross—then returned to Fairfield along the Winslow-Benton rail trail for a total of 8.9 miles. It usually took about three hours. Surprisingly, one of the hardest parts was letting go of the fact that I can drive to Waterville in five minutes and it takes an hour to walk there. It took several trips before I could let it go and not only accept, but embrace, the idea of moving slowly.

We move quickly in almost everything we do these days. Our computer, that seemed so fast when we first got it, is now too slow. Gotta have a new one. Everything has to be faster, brighter, newer. Walking is so old fashioned. My grandfather used to walk to the mill in Shawmut Village three miles away, just to go to work everyday. You have to let go of this notion of old fashion ways so that you can embrace it wholly. And once you embrace it and let go of the need for speed, you start to notice.

Notice what? Things. Which neighbors hang out their laundry and which don't. The shed behind a garage with a sailboat in it. The rock garden with a fountain in someone’s side yard. Things you’ve driven by a thousand times. You notice how your shoes feel. Maybe one toe is being squished a bit or another has arthritis. You notice how that arthritic toe hurts when you start walking, but after 20 minutes it feels better. You also notice that if you stop to chat with someone you meet, when you start up again you have to go through the arthritic pain all over again before the toe joint settles back down. You notice that synthetic pants are more comfortable to walk in than jeans. You take note of where there is shade and what time of day is more comfortable for walking in the heat of summer. You notice your breathing, when and where you work harder. You discover that the long stretch of road your always considered flat is actually a slow steady uphill grade. You find that walking on a dirt road is better than walking on pavement, and walking on mowed grass is even better, while course gravel can be horrible. You notice that some people wave at you from their cars while others don’t. You notice who else is out walking, and you learn when and where they walk just by observing over time. You notice that if you start to sing a song to yourself that suddenly you’re there (wherever there happens to be). Time does strange things, sometimes it speeds up and sometimes it slows down. There’s a lot to notice.

The Hills to the Sea Trail

The Hills to the Sea Trail starts in Unity, Maine, and wanders the hillsides and fields of Waldo County, ending in Belfast near the harbor. It’s about 50 miles long. I thought that before I spend money travelling to England to walk for a week, why not try it closer to home first? I was telling my friend Lisa DeHart about it, suggesting that I was looking for a walking partner. She jumped at the chance. Our schedules didn’t provide a free week to walk, but we could take a day here and there. We found five days scattered over a month to walk the trail.

Starting in Unity we walked through the campus of Unity College, along the edge of corn fields, down country roads, through cedar swamps, over hardwood ridges, and along the berm of many a small farmer’s back 40. It is a landscape I associate with my grandparents—farms, pastures, stone walls (lots of stone walls), cellar holes, and apple trees. We walked by sheep and cows and horses. We encountered eagles, and warblers, squirrels and porcupines. It was a delightful walk. At the end of each day we were tired and had sore feet, but our spirits were always delighted and free of the worries of our perspective worlds, if for only a few hours. At times we discussed our families, friends, paddling, hiking, politics, and the environment. At times we walked in silence. We got a few blisters, experimented with toe socks, and walking sticks. We learned a lot.

Hadrian’s Wall: A Walk Through History

In the fall of 2018 I joined Shawn and Monica for an 86-mile walk along Hadrian’s Wall in northern England. This was going to be my first long walk. Yes, I had walked the 50 miles of the Hills to the Sea Trail, but it had been over the course of a month. Here we were going to walk the 86 miles in nine days. Shawn and Monica had done this walk before, and they were excited to walk it again and share the experience with me. This was a scenic landscape of rolling hills, sheep and cows, and of course, Hadrian’s Wall.

On the Hadrian’s Wall Trail approaching Housesteads Fort

The wall stretches east to west from Wallsend in Newcastle-upon-Tyne to Bowness-on-Solway. Wall construction started in the year 122 and took a decade to complete. The wall was the northwestern boundary of the Roman Empire. The fortification consisted of a deep ditch on the north side, the wall, then just south of the wall a military road, and then a wider second ditch known as the vallum. There was a fort every five Roman miles, a milecastle every Roman mile, and two turrets between each milecastle. Not only is much of the wall foundation still there, so are parts of the forts, milecastles, and turrets. There was a lot of history to explore and contemplate as we wandered by way of pastures, fields, country lanes, and occasional highways.

Feeling prepared for the long walk after spending the summer walking my various loops near home, I was excited to explore a part of the world I’d never seen. I was prepared for proper foot care and had determined what I would carry and what I would leave home. What I hadn’t planned on was my pack tumbling off the table after the TSA inspection at Logan Airport. Having had to remove my shoes for the security inspection, I was still in my socks when the pack landed. The internal framing precisely landed on the second toe on my right foot. It hurt as things like that do, but I shrugged it off, picked up the pack, and dressed my feet. I didn’t think any more of it until after our first day of walking. It hadn’t hurt at all during the day’s hike, but it was excruciating when I took my boot off that evening. The second toe was all swollen with a huge blister, but not on the bottom of the toe like you’d get with a friction injury from walking. Instead the blister was just under the toenail—right where the pack had landed. I sat on the corner of my bed in that delightful B&B in Heddon-on-the-Wall and winced at the thought that I might not be able to walk on.

The first day was our longest day on the trip and most of it was on tarred roads and paths. Did that irritate my toe’s injury enough to end my trip after just one day? When I stood up and walked around my room it didn’t hurt at all, but when I got into bed that night the weight of the sheets almost made me cry. It didn't hurt to step down with the toe, it only hurt when there was pressure from the top. So I got up in the middle of the night because I had to know how it would feel with my shoes on. Could I walk? It was painful getting the shoe on that foot, but once it was on it seemed to protect the top of my toe and I was able to walk without pain. So I tread back and forth in my room in the dark until I convinced myself I’d be able to walk the next day. Finally, I laid down and went back to sleep. In the morning it hurt to put my shoe on, but once it was on, walking was fine. I was good to go. I debated whether to pop the blister. I knew that popping it would relieve the pressure and feel better, but it also opens it to possible infection (which would surely end my trip). When I consulted with Shawn, he said unequivocally to let it be. If we have to walk slower, we’ll walk slower. Let’s not even take a chance with an infection. Good decision. And we didn’t even have to walk slower. Over the next couple days the blister subsided on its own.

Newcastle-Upon-Tyne

We walked through the urban landscape of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, passing beneath its many bridges. While we began our walk at Wallsend, the site of the Wallsend Roman Fort, we didn’t actually meet up with the wall until the end of the day at Heddon-on-the-Wall. From there we followed the wall, passing milecastles, turrets, temples, and other forts—all in various states of past archeological excavations. We walked through pastures and barnyards, along sills and over crags with north-facing escarpments. England is famous for its gray damp weather, but our weather was for the most part good. We had a morning shower on our second day, but the sun soon prevailed. And on the day that it was cloudy, there was a strong, surprisingly warm wind that swept over us, keeping the chills at bay. The only rainy day was our final one, in Carlisle.

Chesters Roman Fort

My favorite fort was Chesters Roman Fort. That’s probably because it was one of the first forts we really explored. Shawn and Monica had been there before, and Shawn was helpful sharing the highlights. The museum was fascinating, but the baths by the river were the centerpiece of the site. It had been a long day, my feet were tired, and when Shawn and I sat among the stones that had been the foundation works of the Roman baths, I imagined many a tired soldier sitting in the same spot amidst the soothing waters of the bath relaxing tired muscles. We lacked the steam and the water of the baths, but we sat on the same stones, we had the warmth of the late afternoon sun, and the delight of the River Tyne slowly passing by. I sat there laughing and joking with my friend and walking companion, just as many a Roman soldier had done nearly 1,900 years ago. The baths seemed to still hold their magic after all these years.

Sycamore Gap in the rain

About midway through the trek, we passed the iconic tree in Sycamore Gap, the spot that Kevin Costner made famous in his version of Robin Hood. We reached it in the late afternoon under a grey wet sky in the drizzling rain. Its beauty and mystique seemed only amplified by the dour weather. The next day, we had a layover day at the Twice Brewed Inn in the hamlet of Once Brewed. During the free day, we walked to Vindolanda, a Roman fort that predated the wall and is currently under active archeological excavation. The site has an extensive museum as well as some reconstructed walls and structures. Perhaps the most impressive discovery here to date are handwritten letters, penned by soldiers from far-off lands stationed on this northwestern frontier almost 2,000 years ago. These were found on postcard-sized thin wooden tablets buried in the wet soils around Vindolanda. The writings were prosaic in that they were not official Roman documents but rather personal letters. They recounted birthday parties, grocery lists, and letters home requesting things such as new socks and underwear! More than 700 of these correspondences have been discovered since the first was uncovered in 1973. Walking the wall to discover these letters from the past felt like stepping into the past in a most literal sense. We walked there, just as many of those soldiers did so long ago.

So where is the wall, when do you feel you are there? Is there a spot that one should not miss? Maybe Housesteads, maybe Vindolanda, maybe Sycamore Gap. Maybe there is no spot. To understand the past, you have to contemplate time, and perhaps you have to spend some time to really do that. There are certainly other ways to do this beside walking, but walking is a great way to step forward and ponder the past, walking the same landscape as the Romans did 1,900 years ago.

As one walks the crags and sills of Northumberland today, there is ample time to consider the fear the Romans held looking north towards Scotland. Watching from the milecastles and turrets for the movements of the Picts and Caledonians—the barbarians who had to be held at bay, perhaps at great cost—the soldiers found themselves in a harsh northern climate far from loved ones. They must have often wondered why. So where is the wall? It’s really in the past. Today we only have vestiges of what once was, but with time, a bit of wind in your face, and tired feet, climbing those crags alongside a crumbling wall, for a moment you can step back in time and touch a piece of what once was.

The walk along the wall is a reflective experience at times. Energy is spent contemplating the world that once was, but I found it also made me consider my own past. Walking with a friend I’ve known since childhood, I couldn’t help but wonder why some friendships last while others fade and disappear. Shawn and I have discussed this at times, and we both feel it’s largely because our friendship has grown and changed through the years. While we can both reminisce about our common pasts, we seldom do. Hadrian’s Wall taught me to appreciate the past and to understand where I came from, but at the same time, to keep an eye forward and to keep on walking. As Shawn so often says about our friendship, “Whenever we get together, it’s like our conversation just picks up and we keep on going.” Walk on.

For galleries of both the Hadrian’s Wall walk and the Portuguese Camino click here.

Pilgrimage: The Portuguese Camino

About the time that Shawn had suggested that Laura and I should join him and Monica for a walk in England, we saw a movie titled The Way. It was about a father following his late son’s dream of walking the Camino de Santiago—The Way of St. James—from Southern France to Santiago, Spain. When the film ended, I said to Laura, “I want to do that.” I started learning more about the Camino, and it turns out there are several Caminos, all ending in Santiago. Historically, it was a religious pilgrimage, and people walked it from wherever their home was. The tradition has revived in recent years, and the most popular route is the French Camino starting in St. Jean Pied de Port. It’s 500 miles and requires roughly five to six weeks. I wasn’t as intimidated by the distance as probably I should have been, but I knew I couldn’t afford to take that much time.

The option was to start somewhere along the way. People did that all the time, but if I’m going to walk it, I want to walk it. The whole thing. I had friends interested in walking it too. Lisa DeHart, my walking companion whom I walked with on the Hills to the Sea Trail; Lisa Lisius, a canoeing friend; and Larry Berz, a fellow astronomy educator. But the logistics got complicated, and the years went by. Then Ben called and asked if I’d like to do part of the Camino with him, a father-son adventure. He could only swing about two weeks, so we’d have to decide on a starting point somewhere along the way, unless . . . That’s when I got the idea of doing a different Camino, one less traveled, perhaps one a bit shorter.

In October 2019 Ben and I flew to Porto, Portugal, to walk 140 miles of the Portuguese Camino to Santiago, Spain. We started at the cathedral in Porto, where we got our credentials stamped. The credentials are basically a Camino passport. To receive an official certificate of completion in Santiago, you need to have at least two stamps in your credentials each day, proving that you’ve walked at least 100 miles to qualify. With our first stamp we began our father-son pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela.

Taking the train out of the city felt like cheating, but we read that the first 10 miles were through industrial zones and less-than-appealing urban sprawl. And besides, from the cathedral is was over 30 miles to our first inn. The train ride would bring it down to under 20 miles, a much more doable first day of walking. Leaving the train station we took a wrong turn and spent the first hour quite lost. We knew the general direction to go, so we went that way. Eventually we found the first of many Camino signs. Relieved to finally be on the trail, I had Ben pose beside the sign. We were now, finally, walking the Caminho, as it’s called in Portugal.

The Caminho is quite different than Hadrian’s Wall: we weren’t walking through pastures, but instead we strode mostly along roads and byways. Sometimes busy highways, but usually along quiet country lanes and frequently on dirt roads and paths. The few animals we saw were always penned. The one constant along the way were the grapevines. Everyone grows grapes—in their backyards, in fields, and across arbors that we sometimes walked through. We tasted a few and they weren’t of the eating variety—they were clearly for making wine. We learned that everyone makes wine, both for themselves and their families as well as for profit. The Caminho was also lined with flowers, cork trees, and olive groves. Churches and chapels were everywhere. Even small villages would have a couple churches. The landscape was rolling hills with lots of greenery and running water. The people were friendly and proud. We were told not to speak Spanish to them, because it’s viewed as an insult. Portuguese is not a dialect of Spanish. They would prefer that pilgrims speak English instead of Spanish, if you don’t know Portuguese, that is. I knew a few words in Portuguese, but Ben thrived at attempting to communicate and they loved him for his propensity to try. They often smiled and politely told him that he was learning Brazilian Portuguese and that was not what was spoken in these parts!

The Way of St. James

Many churches, buildings, and homes were covered with colorfully painted tiles. Some were solid colors, many had geometric designs, and some depicted scenes and stories. Each was unique. Some of our accommodations were very Old-World, restored manor houses with stately courtyards, some were modern hotels, while a couple were more like truck stops with motel rooms. All were clean and served good food. The first time we stayed in an inn of the truck stop variety, I felt cheated. It took away that European mystique of the old world. But as I thought about it, it was a good mixture of old-world mystique, modern city hotels, along with a couple of highway motels thrown in for good measure. Probably a much more realistic way to get to know the real Portugal and Spain. No place is really all old-world romance.

A typical pilgrim meal

We ate pilgrim’s meals each night wherever we stayed. The food was all good, though fairly plain. Each meal usually consisted of soup, bread, a main course of fish or chicken or pork, veggies, rice or potatoes, a bottle of house wine to share, and then dessert with coffee or tea. When we entered a dining area we were never asked if we were pilgrims—it was understood. We were given the pilgrim menu and ate heartily. When non-pilgrims entered the dining room, they were given a different menu with more options and fancier foods and wines. When we were in the larger cities of Porto, Tui, and Santiago, we were on our own for meals and had the fancier meals too, along with the higher price tag.

Ben and I walked together and talked about anything and everything. From music to grad school to work to women to friends to politics and religion. At times we would walk for more than an hour without a word. I often stopped to take pictures and Ben would keep walking. We might walk some distance before coming back together. We developed a rhythm that worked well. We never became so separated that we didn’t know where the other was, but we didn’t feel the need to always walk side by side.

We both decided not to bring a computer along, which was a good decision. We had our phones, so we could make calls, check our email, and get weather reports. But we both knew that if we had our laptops we would have spent each night on them, catching up on work, or processing the day’s photos. Instead, we ate leisurely dinners, enjoyed the local wines, had good conversations, and sometimes even stargazed. We let the work world go, letting ourselves explore the world that the Portuguese Caminho presented. It was delightful in so many ways. Exploring churches, museums, shops, and cafés became a daily routine. Just one foot in front of the other. And as Thoreau suggested, when we “entered the woods or the caminho, we were there, body and soul.”

We met other pilgrims each day and several we periodically re-encountered, which sometimes led to sharing a beer or wine or dinner. There was always much to talk about with other pilgrims. Where are you from? What brought you here? Where did you start your trek? Some were their for strictly religious reasons, like the woman who had battled breast cancer and had prayed for recovery and was now walking the way of St. James to acknowledge her faith. Others were walking for exercise, and others were there because it was another long trail to check off on their list of long trails to walk. Why were we there? To walk. To be present where we were walking. To spend time together, father and son. Two weeks alone with your adult son is a rare gift, and perhaps two weeks alone with your father is a gift as well. I like to think that we both saw it as such. It was a great trip, one like no other.

Before we entered Santiago, Ben suggested we shave our beards and go into the city with fresh new faces. Somehow, it felt like a meaningful thing to do—we couldn’t exactly say why, but it was one more way to connect with each other and the Way of St. James.

Reaching the square in front of the cathedral at Santiago de Compostela was a moment that I’ll never forget. We had walked 140 miles to reach this spot. There were pilgrims who had walked greater distances than us, and those who walked much less, but we all converged before the cathedral and shared a moment that was meaningful in ways that many of us couldn’t articulate. It moved me to tears, then to smiles, then to laughter. Then we went to a café for lunch, coffee, and to consider where we’ve been.

The Way of the Grapevine

Covid-19

It’s 2020. There have been lots of short walks around town, but no big trips this year, just dreams of post-COVID wanderings. Now that Laura has had knee replacement surgery, our hope is to walk the English Camino from the northern shores to Spain to Santiago, then on to the End of the World—Finnisterre, a point of land that extends into the Atlantic, where many pilgrims traditionally end their pilgrimage. We would also like to walk together in England, Scotland, or Wales. So many walks await us. But until the time comes, we’ll walk here at home and dream of far away lands that we may one day explore on foot. Together.

“I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking, that is, of taking walks,—who had a genius, so to speak, for sauntering: which word is beautifully derived “from idle people who roved about the country, in the Middle Ages, and asked charity, under the pretense of going á la Sainte Terre,” to the Holy Land, till the children exclaimed, “There goes a Sainte-Terrer,” a Saunterer,—a Holy Lander.”